Article by the Mekong School Team and Lam Phuong Mai

Photo by Junyi Yu

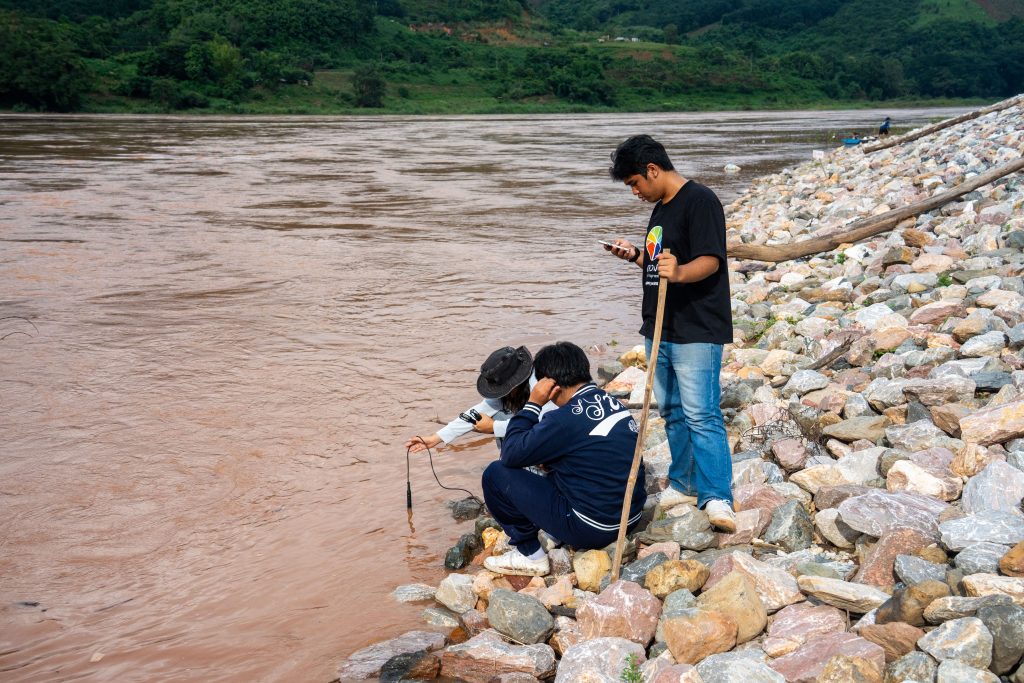

Chiang Khong, Thailand – In response to rising environmental concerns and a lack of publicly available data, high school students from Chiang Khong and nearby areas participated in a citizen science initiative organized by the Mekong Youth Program. On July 6, the students voluntarily participated in a hands-on water quality monitoring activity, using test kits and field tools to examine conditions at seven key sites along the Mekong River and its northern tributaries—locations increasingly affected by upstream mining activities and transboundary pollution.

The testing sites included Chiang Khong’s stretch of the Mekong River, the Kok and Ruak River mouths, Kok River, Koh Pilung, Pong Khong, and the Golden Triangle. These locations are not only ecologically significant but have also become focal points of concern due to increasing transboundary pollution, particularly from upstream mining operations in Shan State, Myanmar.

The alarming events of the red tide floods in September heightened the urgency behind the initiative. When the waters receded later that year, fishermen at the mouth of the Kok River discovered abnormally sick fish—such as Bagarius bagarius, naked catfish, and Cirrhinus microlepis—many with visible spots and discoloration on their bodies.. However, instead of launching a transparent investigation, Thai authorities dismissed the incident, claiming the fish were “from Laos” and unrelated to domestic environmental conditions. This denial, offered without evidence, sparked widespread public frustration and further exposed the critical gap in official accountability. This refusal to take responsibility has caused widespread frustration and underscored the need for accessible, community-driven environmental monitoring.

Later, Thailand’s Pollution Control Department (PCD) acknowledged that Arsenic had been detected in the water. However, the agency withheld all related data from the public, offering no explanation, no reports, and no action. This lack of transparency prompted community members to take action. On March 2, 2025, local residents launched a grassroots campaign demanding answers, driven by the belief that people have the right to access environmental data that affects their health, lives, and livelihoods.

Their concerns were validated when, on July 3, the Mekong River Commission (MRC) published its own findings. The report confirmed that arsenic concentrations in several sites across northern Thailand’s Mekong tributaries had exceeded the standard safety threshold of 0.01 mg/L and were classified as moderately serious. The testing, conducted by the MRC Secretariat, indicated what locals had long feared but were never officially told.

Photo by Ruikang Wang

In light of this confirmation, the July 6 event organized by the Mekong Youth Program became not only timely but essential—a direct community response to the lack of transparency and urgency from official channels. The program is not just about bridging the gap between science and society—it’s about granting young people and their communities access to environmental knowledge and tools. It equips students with the skills to monitor water quality, ask critical questions, and make sense of the environmental challenges their families and communities are facing. The event was not just a data-gathering exercise—it was an act of empowerment. By learning how to conduct the tests themselves and physically holding the results in their hands, students gained a more serious understanding of what their elders have long been worried about. And with that understanding comes the ability—and the confidence—to take meaningful action.

“The process is more important than just getting the result,” said Bird Researcher and Mekong School Volunteer Chak Kineesee. “By doing it ourselves, we understand how information is created and shared—and why it matters.” Through hands-on testing and guided reflection, students explored topics such as data collection, transparency in science, and communication of findings. The program reframes science not as a subject locked in textbooks or labs, but as a living tool in everyday life—something anyone can learn, apply, and share.

This approach has resonated deeply in Chiang Khong and beyond. When students see science as something they can do—on the river, in the field, with their peers—it shifts the way they learn and live. It helps them ask better questions, recognize environmental risks, and work on solutions together with their communities.

Photo by Ruikang Wang

At its core, the Mekong Youth Program promotes a simple but radical idea: knowledge should not be exclusive. Communities have the right to understand what affects them, and youth have the power to lead that change. In an era of climate crisis and environmental injustice, this kind of accessible, participatory learning isn’t just beneficial—it’s essential.