Heavy metal contamination in the Mekong River from May to September 2025. The situation remained unchanged.

Report on the measurement of water quality by Mekong Youth Program, Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge, May-September 2025

On the 6th Saturday and Sunday, 7th September 2025, (Chiang Rai Province), the Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge also opened its mobile laboratory for the fifth month of September. Youth volunteers, high school students from Chiang Khong Wittayakhom School and Huai So Wittayakhom Ratchamangkla Phisek School, along with institute volunteers, aimed to collect samples and examine water quality in the Mekong River from Sop Ruak, the Golden Triangle, to Kaeng Pha Dai.

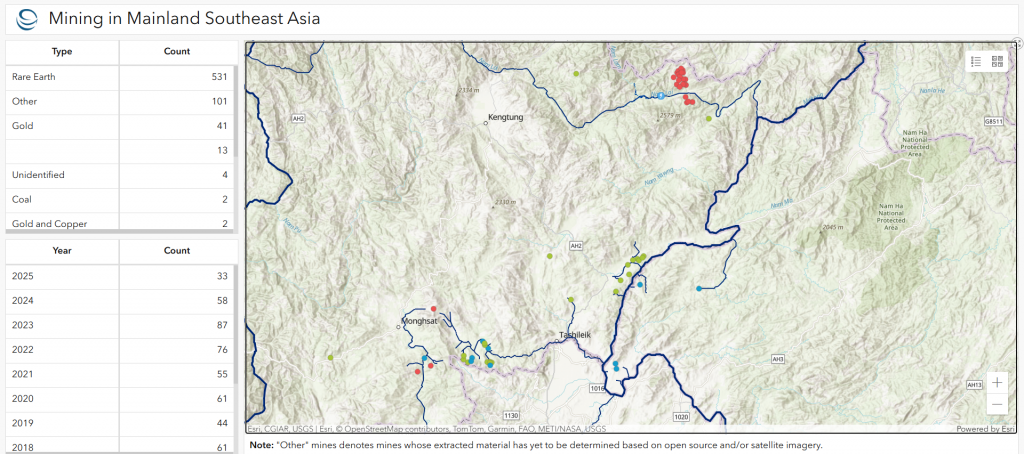

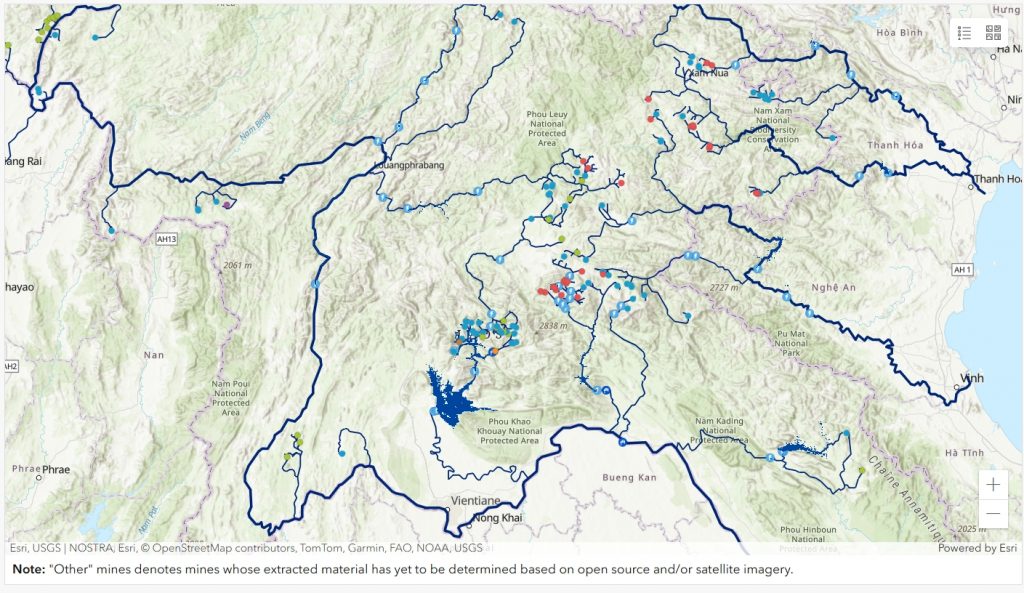

We met at 7 a.m. to discuss our expectations. The Mekong River situation, including hydropower dams, toxic contamination from upstream mining, and Smog, is a transnational issue. It’s a major problem in the Mekong Basin and reflects a global issue. We also shared important news: our friends have used satellites to search the Loei River basin and found 57 rare earth mines, including 31 in active and inactive mines in Wa State and 26 in National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) territory. This news aligns with a report by the Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF) on August 25. revealing satellite images from May 2025 and additional video footage showing 19 rare earth mines in Mong Yong District, eastern Shan State, under the control of the Mong La Army. This confirms the existence of an upstream mine approximately 125 km north of Sop Ruak, at the mouth of the Loei River flowing into the Mekong River.

Image credit: Stimson Center: Showing the discovery of mines at the headwaters of the Kok, Sai, Loei, and other rivers in the northern Golden Triangle area, using open-source data and satellite imagery. Rare Earth mines (orange dots), gold mines (light yellow dots), coal (brown dots), gold and copper mines (light blue dots), potash, cement, and other unidentified mines (blue dots) have been discovered, including in the Xieng Khuang area of Laos.

Our water monitoring station on September 6th, the weather was pleasant, leaning toward hot, and the sky was blue. A young boy Volunteer named Budu described the first water monitoring station as follows: “The sky was blue with a few clouds on the horizon. The water level had dropped to the point where mud was visible. The water was thick and murky. There were the sounds of birds, boats, and cars. A cool breeze blew. Black pigeons flew to the riverside balcony. Along the riverbank, flooded grass was clearly visible, brown and separated from the other plants (green). Garbage floated in the water…” Similarly, in the records of P’Praew, P’Praewa, P’Phum, and P’Potae, they all said that at this point, the trees along the riverbank were still green. The water had receded, revealing mud. The river was turbulent, with branches and garbage floating in the water. There were living creatures: fish, fishermen, insects, ants, and garbage in the crevices of the rocks on the riverbank embankment.

As we set up our equipment and collected water samples, awaiting the results of the measurements, we overheard a crucial conversation between volunteer guides from the Mekong School and villagers sitting at the pier pavilion. They said that several agencies had come to measure the water, including taking blood samples for contamination testing, but they didn’t know what the results would be.?

Sriwan Pier, Pak Nam Ruak, is not far from the second pier on the Mekong River near the Buddha image “Phra Phuttha Nawalanthue” (Four countries’ Chiang Saen Buddha image) in the Golden Triangle. At the exit, tourists are waiting to board the boat. We went down to collect water on a raft. The water in the Mekong River flows strongly and swirls. The water is murky, with wood fragments and floating garbage. We brought the water to test under the Buddha image, and there were traces of high mud stains from the great flood in September last year (2024). As we were nearly finished measuring the water level, the Chinese cargo ship Maoyuan 2 sailed by. The waves crashed against the shore hard. There were very few birds singing. Mostly the sound of boats. The sun was hot, and there was almost no wind. The Giant Mimosa trees by the river were covered with garbage hanging everywhere. Much of the garbage was stuck to the pontoons. The clouds on the horizon were starting to rise.

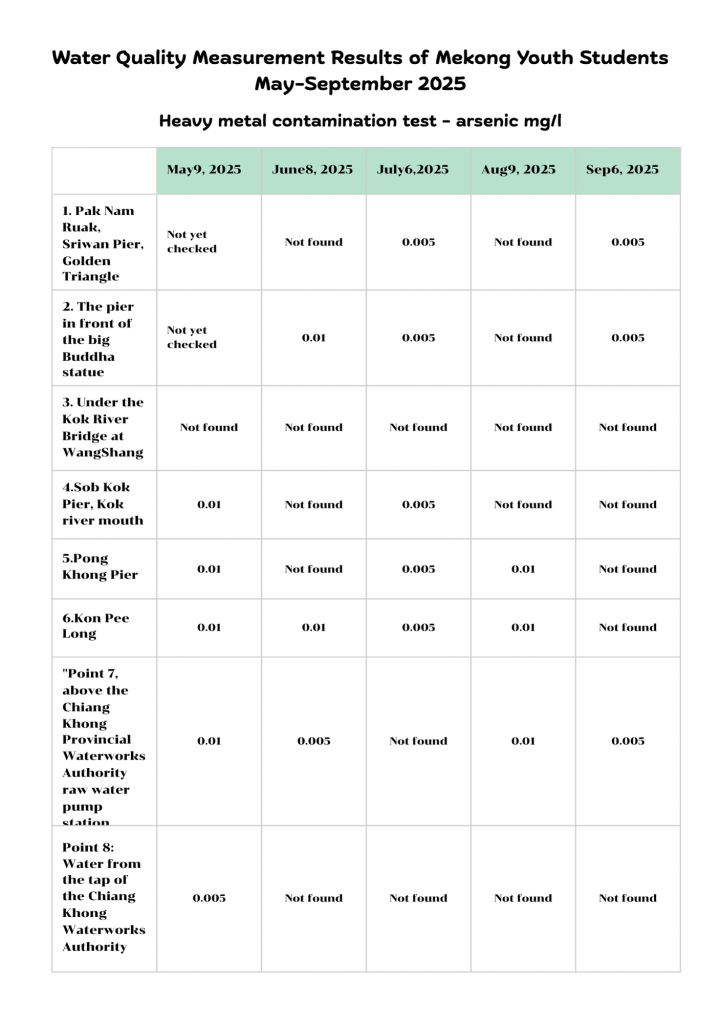

At the first point, we have measured arsenic levels four times on June 8, July 6, August 9, and September 6. The arsenic levels were found to be 0.005 mg/l twice, on July 6, and this time on September 6. However, we did not detect arsenic levels on June 8 and August 9.

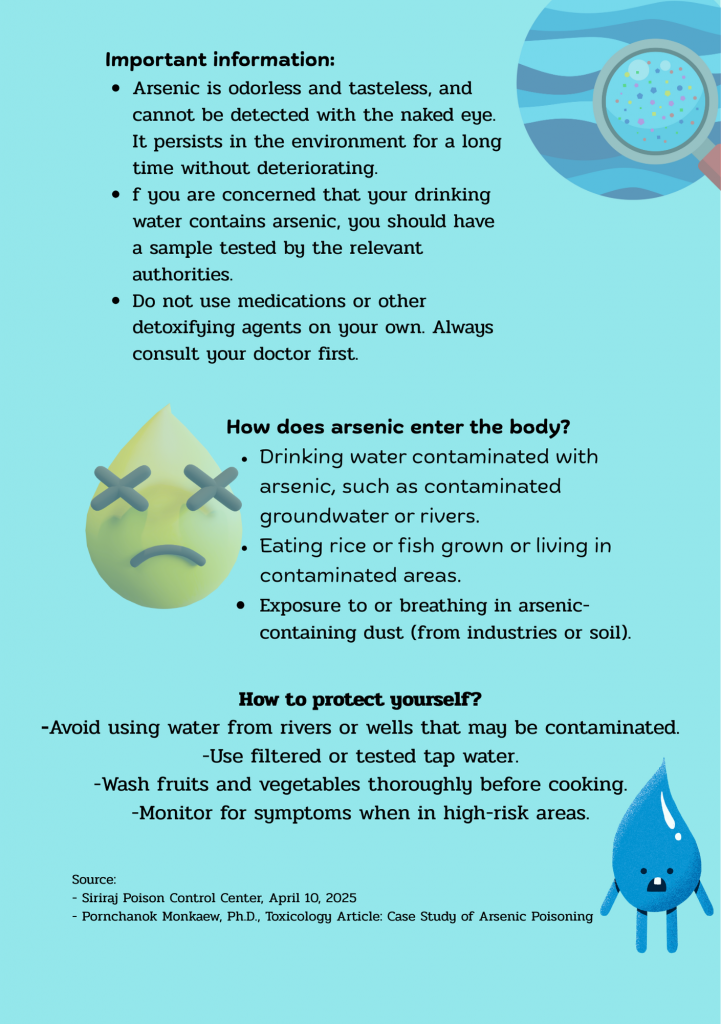

Our young investigators have examined water quality across a variety of indicators, but in this month’s report, the fifth month of our water quality monitoring and learning program, we’ll only cover the heavy metal “arsenic,” which isn’t a rodenticide.

Arsenic is both a metal and a nonmetal. It occurs in both inorganic and organic compounds. It occurs naturally in soil, water, and rocks, and in man-made sources, with levels three times higher than in natural sources, such as wood preservatives, insecticides, herbicides, and mineral smelting.

At the second location, a pier on the Mekong River near the “Phra Phuttha Nawalan Tue” Buddha image in the Golden Triangle, we have also conducted four measurements. The first reading on June 8th was 0.01 mg/l, the second on July 6th, and this time on September 6th, the reading was 0.005 mg/l.

We headed to the third point under the Kok River bridge. Clouds were beginning to gather. Traces of mud from the highest flood level of September last year appeared on the bridge pillars. The water was thick and murky, flowing fast. There were no boats, only traces of flooded grass. There was so much mud that there were hardly any birds, only the sound of cars driving on the bridge. It was neither hot nor cold, with a slight breeze. There were a few Giant Mimosa trees by the water, a few bushes, mostly arranged rocks, and a little floating trash. We even saw a local cat. In the notes of a young boy Volunteer named Budu, and the Mekong River youth, they also wrote that there were dead trees, lots of mud, animal footprints, fine mud, and trash piled up in various corners.

Under the Kok River Bridge in Ban Wang Sang, Ban Saeo Subdistrict, Chiang Saen District, five tests with our equipment showed no arsenic. After collecting water samples for testing under the bridge, we continued to the Ban Sop Kok Pier, at the mouth of the river near the second Chiang Saen commercial port. Don Chang Tai is located on the left. We collected water and tested the results. This is the third reading.

This Ban Sop Kok Pier is the fourth. We tested five times, with a reading of 0.01 mg/L on May 9th and 0.005 mg/L on July 6th. The readings were negative in June, August, and September 6th.

We headed to the fifth point, the pier in front of the Mae Ngern Health Promoting Hospital, Ban Pong Khong, Mae Ngern Subdistrict, Chiang Saen District. Our students’ notes said the sky was clear, windless, clouds gathered in lumps, and hot. Along the pier were trees: champa and paduak. Villagers came to fish, and children also came to practice fishing at the pier. There was trash clinging to the dry bushes along the water’s edge. There was the sound of birds chirping, the water flowing swiftly, fish, and ants crawling on the rocks. The banks were still lush and green, with insects…

We have measured the water at this point five times, with a finding of 0.01 Mg/l on the first monitoring trip, May 9th, and last month, August 9th. On July 6th, we received a reading of 0.005 mg/l. This was a shock to us from the start. However, we received no reading on September 6th.

Station 6 is Khon Phi Long, opposite the mouth of the Yon River, Rim Khong Subdistrict, Chiang Khong District. Construction on the Mekong River retaining wall has been ongoing this year. Today, the foreman at the construction camp informed us that it’s finished, with only a little work remaining. Our little detectives found a ladder down to the pier at Hat Hai Pier, opposite the mouth of the Yon River, where you can see a small mine at the mouth of the river. This time, it was easier to get into the water than last month. There were a lot of rocks, and the sand along Hat Hai Beach looked like it had a glitter like diamond dust.

Measurement results for the past five months at the Pak Nam Yon-Khon Phi Long point showed readings of 0.01 mg/l on May 9, June 8, and August 9. The only time the reading was 0.005 mg/l was on July 6. No readings were found on September 6. However, this clearly reflects the arsenic contamination at this point, which has persisted for four months and continues to accumulate more each day the river is still flowing.

Khon Phi Long is a site of islands and rapids, and a healthy ecosystem. It’s a deep water source with spawning grounds for the Mekong Giant catfish. It’s a key location for large cargo ships, each weighing 500 tons, to open their waterways for transporting cargo from China to Luang Prabang, Laos, year-round, all season.

This area was a fertile yolk area for the past two decades. This decade, the fish’s fertile home has been compounded by the cumulative impact of water fluctuations that are not in sync with the natural seasons, but by the control of upstream hydroelectric dams and the opening and closing of water for navigation… to the point where local fishing communities have virtually collapsed. No matter how they adapt, it’s dark…

Today, in this decade, we face the risk of heavy metal contamination in the tap water of cities and communities along the Mekong River. We drink, bathe, and use tap water that comes from the Mekong River.

I went back and read the Mekong River Detective’s Guide to Arsenic: The impact of arsenic on the environment and living things has disrupted the river’s ecosystem, altered its ecosystem, accumulated in fish, shellfish, and passed down the food chain, leading to long-term effects on aquatic species. It affects humans and animals, entering the body through drinking water, food, or breath. In the short term, nausea, stomach pain, diarrhea, and dizziness. In the long term, skin cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, kidney disease, diabetes, and skin disorders.

In various review documents, it is worth noting that:

We find ourselves facing increasingly difficult lives. Meanwhile, fishermen who still make a living from the Mekong River, boat people, raft workers, fish farmers in cages on the banks of the Mekong River, riverside farmers, and their communities and towns are all losing income. People are not buying fish, rice, or crops, and are having to buy water for drinking, increasing their expenses due to fears of heavy metal contamination.

We have the right to access clean water, swim in clean rivers. We have the right to access healthy fish and rivers, to eat and live… This is why we’ve come together to measure and monitor the quality of the Mekong River. We also measure other indicators, including visual observation of the overall condition, temperature (°C), dissolved oxygen (DO) (ppm), acidity-alkalinity (pH), total dissolved solids (TDS), salinity (ppt), arsenic (As: mg/l), and ammonia (Am: mg/l). But in the measurement report… We’ll first look at the overall water quality from Sop Ruak to Kaeng Pha Dai (we’ll present the complete report next).

The results of arsenic measurements at Point 7, above the Chiang Khong Provincial Waterworks Authority raw water pump, showed arsenic levels of 0.01 mg/l on May 9 and August 9 in all four of the five tests. The readings were 0.005 mg/l on June 8 and September 6. Only on July 6 is the reading negative.

When we look at measurement point No.8, water from the Chiang Khong Waterworks’ taps from households, for comparison, we found a reading of 0.005 mg/l only once out of 5 times, on May 9.

However, we exchanged opinions that the point where we chose to test water from the mouth of a tributary and the point where the water mixed with the Mekong River were important things for us to use in the comparison, including the mouth of the Ruak River and the mouth of the Kok River. We agreed that we would expand the monitoring points down to the mouth of the Ing River, the mouth of the Ngao River, and Pha Dai in Wiang Kaen District.

On the morning of September 6th, we—meaning myself, Budu, and P’Kai—joined in expanding the water quality monitoring program under the Ing Udom Bridge in Ban Taen, Sathan Subdistrict, Chiang Khong District. The boy’s journal notes that the sky was overcast, with occasional winds. Sometimes it was hot, sometimes cool. There were no trees along the riverbank, just stacked rocks. The water looked murky, with no floating trash, just a few lumps of water floating by. The water flowed slowly, but there were the sounds of birds, frogs presumably eaten by snakes, and chickens. There was only one boat moored at the pier, and there were traces of mud on the steps from the flooding. Across the river, a bank collapsed.

We collected water samples and then worked together to test the water quality. Budu was responsible for the ammonia test, which he had experimented with his older Mekong Youth Student on many occasions. I was responsible for checking arsenic levels from under the Ing Udom Bridge, the Mekong River pier at Ban Pak Ing Tai, the pier of Ban Chaem Pong, along the Ngao River behind Wiang Kaen Intersection Market, the Huai Luk pier at Ban Huai Luk, and Kaeng Pha Dai. We found no arsenic levels, except for Kaeng Pha Dai pier, where a reading of 0.005 mg/l was found.

While waiting for the results, I spoke with the mother of the restaurant owner at Pha Dai. She said that since the news of the contamination broke, she has been unable to sell fish and that fish are becoming harder to find every year. How can we solve this problem?

What does this situation tell us?

I tried to analyze the data with an AI, as shown below.

The results of the analysis of arsenic (As) levels in water sources. The contamination levels at the monitoring points were based on the following criteria:

– The WHO sets the As level in drinking water at no more than 0.010 mg/L.

– Not detected = arsenic levels below the detection limit.

– Moderate: 0.005–0.009 mg/L.

– Borderline: Equal to the maximum standard of 0.010 mg/L.

Severity of contamination:

- The arsenic levels at 0.010 mg/L (points 2, 4, 5, 6, 7) reached the safety line, requiring immediate action.

- The 0.005 mg/L (points 1, 8) were still at moderate levels, but near the maximum limit. Therefore, vigilance should be exercised.

- The site where arsenic was not detected (Site 3) was considered low risk during the monitoring period.

Dry Season Trends

- Decreased water volume → decreased chemical dilution, leading to increased As concentrations.

- Rising temperatures and increased evaporation may stimulate the release of As from sediment to surface water.

- Raw water sources (Sites 7 and 8) may further increase As accumulation if no enhanced filtration system is installed. (And the review of the Chiang Khong Provincial Waterworks Authority’s water quality measurement results: The author added this based on suggestions from participating students, who were interested in learning about the Chiang Khong Provincial Waterworks Authority’s water quality measurements.)

- In the small mining area (Site 6), erosion from mining construction and dredging during the dry season may accelerate As release into the river.

If you’ve read this far, thank you very much for following the monthly water quality measurement report by students and volunteers of the Mekong School for five months.

The Mekong Youth As data is consistent with the Mekong River Commission (MRC) finding that arsenic levels exceeded the standard in four of five randomly selected sites in the Mekong River in July, categorizing them as “moderately severe.” Concentrations of the semi-heavy metal arsenic exceeded the standard limit of 0.01 milligrams per liter. Thailand’s Pollution Control Department’s May 2025 assessment also showed that arsenic levels in the Mekong River were consistent at around 0.025 milligrams per liter (https://www.bbc.com/thai/articles/c39z41j77rdo).

The sources of arsenic are mining along the Kok, Sai (flowing into the Ruak), Yong, Loi, and Shan State rivers of Myanmar, which flow into the Mekong River and into the lower Mekong Basin country.

I’ll conclude my report with the results of a young boy named Budu’s recording at Kaeng Pha Dai:

“The sky is beginning to clear, a cool breeze blows. There are no trees along the riverbank, except for one large tree. Mostly grass and rocks are scattered about. The water is murky, the current is strong, there are rapids, eddies, and muddy trails, indicating a receding water level. There’s no floating trash. There are the sounds of birds, crickets, and water hitting rocks.”

At the Ngao River bank behind Wiang Kaen Market, he recorded: “The sky is beginning to darken, the sun is beginning to set, and it’s cool. There are some trees along the riverbank, mostly small ones (riverside plants), many dead. There are traces of mud from this year’s floods. An uncle brought leftover food scraps to feed the fish. He said that this year’s market flooding was a palm’s width high. Last year, it was up to an adult’s waist (August-September 2024). (There are still) the sounds of birds, cars, and crickets…”

Reported by Nopparat Lamun

Support the Mekong River Youth Activities, Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge, at