On July 12, 2015, in ChiangKhong, Chiang Rai, 13 rice farmers in the Ing-Mekong River basin, academics from the School of Management at Mae Fah Luang University, and international students participated in a discussion on “Opportunities and Challenges of Organic Rice.” This discussion, which had been postponed due to last year’s severe flooding, caused widespread damage to the farm, was held under the “Project to Survey Organic Rice Production, Trade, Consumption, Farmer Health, and Marketing in Chiang Rai Province,” organized by the Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge and the Haihui Poverty Alleviation Center in Sichuan, China. The objective was to identify the situation and identify collaborative approaches to organic farming development.

Mr. Niwat Roykaew, Chairperson of the Chiang Khong Conservation Group and Director of the Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge, gave the opening speech.

“Following the government’s 2016 policy on the Chiang Rai border special economic zone, which declared every sub-district in Mae Sai, Chiang Saen, and Chiang Khong districts as a border special economic zone, the zone prioritized economic and trade, while neglecting environmental impacts and the existing agricultural production potential, such as rice. The development of border special economic zones relied primarily on foreign investment and did not consider the capital base of Chiang Rai’s local communities, resulting in significant impacts. However, if development takes into account the capital base, particularly rice, it will benefit communities both economically and environmentally. This development is closely tied to the preservation of natural resources.

Since 2017, the Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge, the Chiang Khong Conservation Group, has been engaging in discussions with academics and Chinese NGOs. These discussions were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, but we continue to strive to foster collaboration and continuity. In Chiang Khong, there are groups of farmers in Boonruang and Sathan, and we also have connections to Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, as some of our own people work there (Chak Kineesee). We also have a collaborative relationship with the School of Management, Mae Fah Luang University. We have been researching rice in Chiang Rai and nearby areas. This meeting was a discussion to create understanding and jointly explore the direction of organic rice development.“

The direction of organic rice development discussed that day presented several challenges and opportunities, at least five of which were:

- Contamination from adjacent fields: The inconsistent rice farming and the use of chemicals nearby made it impossible to certify organic rice.

Suwit Karahan, President of the Boonruang Forest Conservation Group, explained:

“In the Boonruang area, the government had previously supported organic rice cultivation because it offered a better price. However, it was unsuccessful because it wasn’t truly organic. Farmers were scattered throughout the area, and thus faced problems of contamination from adjacent fields, both in terms of water and chemicals…”

- High costs, yields, and prices are not yet attractive: Despite requiring more care, the income per rai is no different from that of conventional rice farming.

Suwit Karahan added:

“…Today, farmers are farming without much knowledge and are unable to set their own prices. Each year, they plant without knowing how much they will sell for. It’s like they don’t know their own future.”

- Equipment and technology are not appropriate for the area: The supported machinery does not match the characteristics of the local rice fields, affecting efficiency.

A representative of a large-scale farmer in Ban Boon Ruang Tai, Village No. 2, recounted how the previous government supported the formation of large-scale rice farming groups in the area, providing production equipment such as tractors, harvesters, gliders, and balers. Some members of Boon Ruang joined the group during the period before the COVID-19 situation. Members of the group farmed both their own fields and those rented under the group’s name. In addition to equipment support, they also supported seeds and precision farming. However, the group ultimately failed for several reasons. For example, members’ fields were not contiguous, creating the potential for contamination from adjacent fields, preventing them from being truly organic. Some of the equipment provided was unsuitable for the area and thus unusable, such as a combine harvester. The rice paddies in our area differ from those in the central region, and the tractors could not climb over them. (He cited the “Hundred-Million-Baht Rice Field” project and the representative who promoted it, which guaranteed a rice price of 12 baht/kg, but which disappeared after the COVID-19 situation.)

Uncle Suwit said, “There’s one issue I’m interested in. If this can be adjusted, it could be a significant help. The disadvantage of the current rice planting machine is that it uses 15-day-old seedlings, which is too short a lifespan. They are difficult to care for in case of flooding. I think that if this machine were used with 1-month-old seedlings, the disease resistance of the planted seedlings would be better.”

4. Lack of knowledge and cost management: Farmers lack true knowledge about managing their own costs and health.

Uncle Jit, a representative of a large rice farmer from Ban Boon Ruang Tai, Boon Ruang Subdistrict, Chiang Khong District, stated:

“I’m interested in adapting to organic rice farming. Is it really possible? How?”

Uncle Jit stated, “I farm on 160 rai of land, producing 132 tons of rice (over 1 million baht in income). I farm twice a year. I grow RD22 (a short-lived rice variety, 100 days, hard rice sent to the factory, yielding 1,100 kg/rai, selling price this year at 8 baht per kg). I also grow RD6 (an edible rice variety).“

Uncle Jit wants an instructor to teach about organic rice farming, partly because of the good price. It’s also a way to reduce chemical use, which means lower costs and is safe for farmers, buyers, and consumers. He also wants to support short-lived rice varieties. In the Boon Ruang area, there’s a growing demand for rice farming three times a year, but this hasn’t been achieved yet.

5. Limitations from water systems and seasons: Changes in irrigation systems and natural disasters, such as floods, affect organic rice cultivation.

Uncle Suwit said that while large-scale rice farming receives equipment support, there is no budget for maintenance or management practices. He noted that he has some resources to generate income, such as a straw baler provided to community members, but the income is limited. The flooding in 2024 further severely damaged the rice paddies.

“Rice farming is not as efficient as it used to be. There’s no fermentation of the soil as we used to, as we have to work more quickly because the adjacent fields have already started. The fields used to not have as much grass as they do now, and there’s no need to rely on herbicides like today.”

Mind, a young person interested in returning to her hometown of Chiang Khong, grew up in a farming family, but didn’t farm herself. She graduated with a degree in agriculture and wanted to return to her hometown to farm. Her family didn’t trust her and wanted her to work elsewhere, so she started by working on a small plot. While working, she encountered problems with neighboring plots that used different farming systems. Sometimes they would push up the ridges, and the timing of water releases didn’t match up. She once invited him to do the same thing, saying it was healthier, but he dismissed it as trivial and contrary to his habits. She believes that using the same system would reduce conflict and significantly reduce the obstacles to her organic farming.

Ms. Kruawan, a farmer representative from Mae Chawa Tai Subdistrict, Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, said she came to participate for several reasons. Her brother (Chak Kineesee, a volunteer at the Mekong School) convinced her that she could succeed. Her daughter, now back home, is running a tea factory for sale domestically and exporting to Chile. Chile has also inquired about Thai rice, as the Chilean market lacks Thai rice. Furthermore, her community previously formed a certified organic rice group, but the group failed to achieve this goal. Beyond price and support, she doesn’t know the other reasons. Lessons learned from this group should be learned as a guideline for further development. She plans to start again and seek support that inspires farmers, both in terms of price and health.

The most common problems encountered in organic farming are high costs and the need for more care, but the yield and price are almost identical to those of conventional rice. This is compounded by the fact that organic rice farming is not done in large scale, contiguous plots. The current use of water from irrigation systems differs from the former water systems. These two factors contribute to contamination, as well as an imbalance in the water system. There is little water in the fields during the dry season and flooding during the rainy season. Furthermore, many rice varieties that we used to see and eat have disappeared.

Nirada, a young person from the Ing River basin in Ban Chanchawa Tai, Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, does not know rice due to living outside the community. She is in the early stages of producing Assam tea for sale, starting from the upstream to the downstream. Currently, she is constructing a packing house. Next, she is interested in selling some of her community’s rice, as she believes this is a product that her community already has. She said this is a time for learning and research, and believes that when the time comes, she will coordinate with the authorities to improve the greenhouse to meet the required standards.

Mai, an intern at the Mekong School, said, “Vietnam has similar problems to what many people are talking about. Vietnam has a similar system to Thailand. The government supports large-scale rice paddies. Rice cultivation at irregular intervals also causes similar problems. There is also the issue of middlemen driving down prices.”

Chak Kineesee, a volunteer at the Mekong School and coordinator of the organic farming community for the survey project, said, “Going back to the past is difficult because we still think about the old methods. We don’t know how much we’ll earn from farming, and we won’t get rich because the price of the product is low, as we let them set the prices. Moving to organic farming can’t happen overnight. We don’t know how much profit we’ll make from farming today. We haven’t yet calculated costs. We need to factor in our own labor costs and determine the level of profit we aim to achieve. We don’t often discuss what we need to supplement our efforts to achieve our goals. We don’t even consider our own health costs. That’s why farmers today aren’t rich. The only ones who are rich are the widows (fathers who use chemicals so heavily that they die from poor health, leaving their earnings to their widowed wives. This situation occurs in many parts of Thailand. We haven’t yet considered new options.”

Looking at the opportunities from the discussion that day, that the gathering of villagers, academics, and international students reflected a shared interest in developing organic rice as an opportunity that could lead to some future opportunities.

Leo Baldiga, a PhD student, said, “I’m a student currently pursuing a PhD. I’m interested in integrating technology into agriculture, and I think it could also be used to help organic rice farming. Regarding the issue of contamination discussed, I believe the use of drones to spray chemicals is a significant factor contributing to contamination. It’s clear that contamination can occur in many ways, including soil, water, and air.”

We therefore had the opportunity to visit the farm and learn from the organic farming community that was going to join us that day. However, due to heavy rain that suddenly flooded the road into the village, we were unable to join them. They were the Ban Thung Tom Organic Farming Group, Don Chai Subdistrict, Thoeng District, Chiang Rai Province. We also visited and talked with the Ban Mae Jua Tai Organic Rice Group, Village No. 5, Mae Suk Subdistrict, Mae Chai District, Phayao Province.

Chak Kineesee, the community coordinator, visited both areas in mid-September 2015. He recorded that:

The Ban Tung Tom Organic Farmers Group in Don Chai Subdistrict, Thoeng District, Chiang Rai Province, is motivated to produce organic rice and other organic foods because they want healthy food for their modern families. They used to live in the big city but want to farm and raise animals on their own rice field in their hometown. They are concerned about the health of their aging mother and young children. They want to return to farming without chemicals on their mother’s land in their hometown because the environment in Ban Tung Tom has good air, abundant water, rice fields, community forests, and streams. They are currently able to work online. Bangkok is a big city with a less pleasant environment than their hometown in the countryside. Food is expensive, and they are unsure about safety. Life is fast-paced and competitive. Therefore, they want to produce safe food for themselves to eat. If they have a lot, they might sell it to generate income.

Initially, the project was conducted within the community itself, as most people lacked a thorough understanding of the impact of agricultural chemicals on themselves, their families, the environment, soil, water, air, and food consumed in their village. Therefore, they worked with the Don Chai Subdistrict Health Promotion Hospital to promote the consumption of safe and herbal foods in the community. They also studied health and blood chemical test data from community members. They found that most of the chemicals in their blood were due to food products that were chemically treated. This was coupled with information from various government and academic media about illnesses and diseases that threaten the lives of farmers today. They also explored advancements in processing, adding value, developing marketing strategies, and expanding sales channels through online media.

Developing production and processing products to reduce costs, promote self-reliance, and increase value.

- Growing rice using the “throw-and-dry” method instead of broadcasting and transplanting rice.

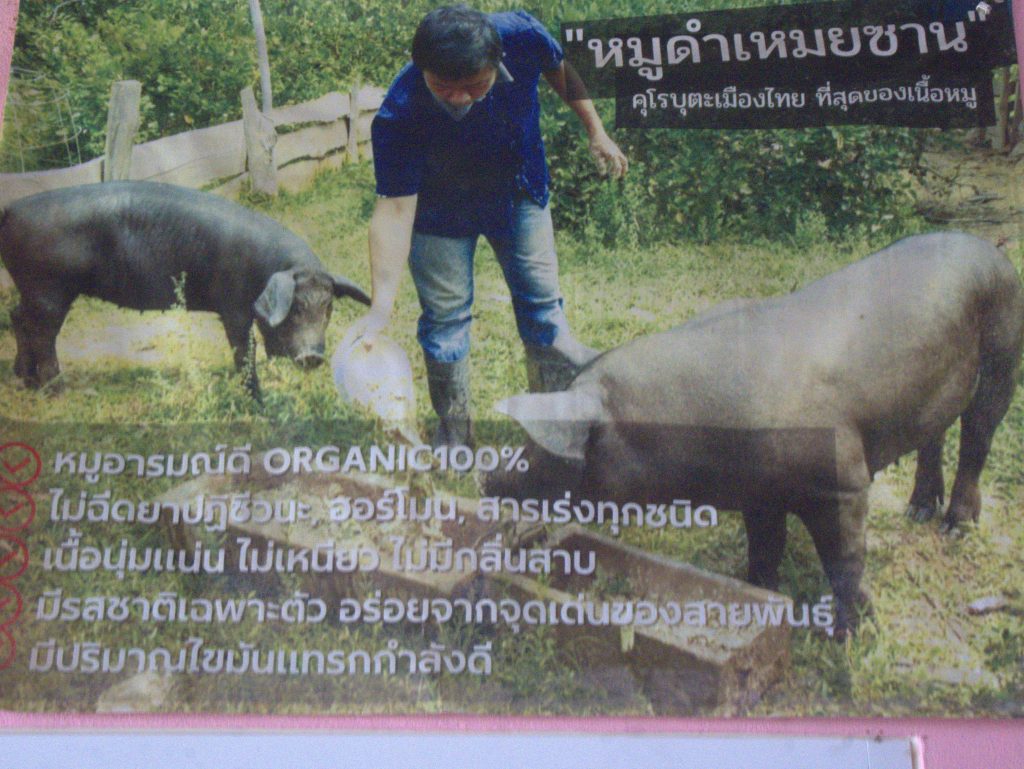

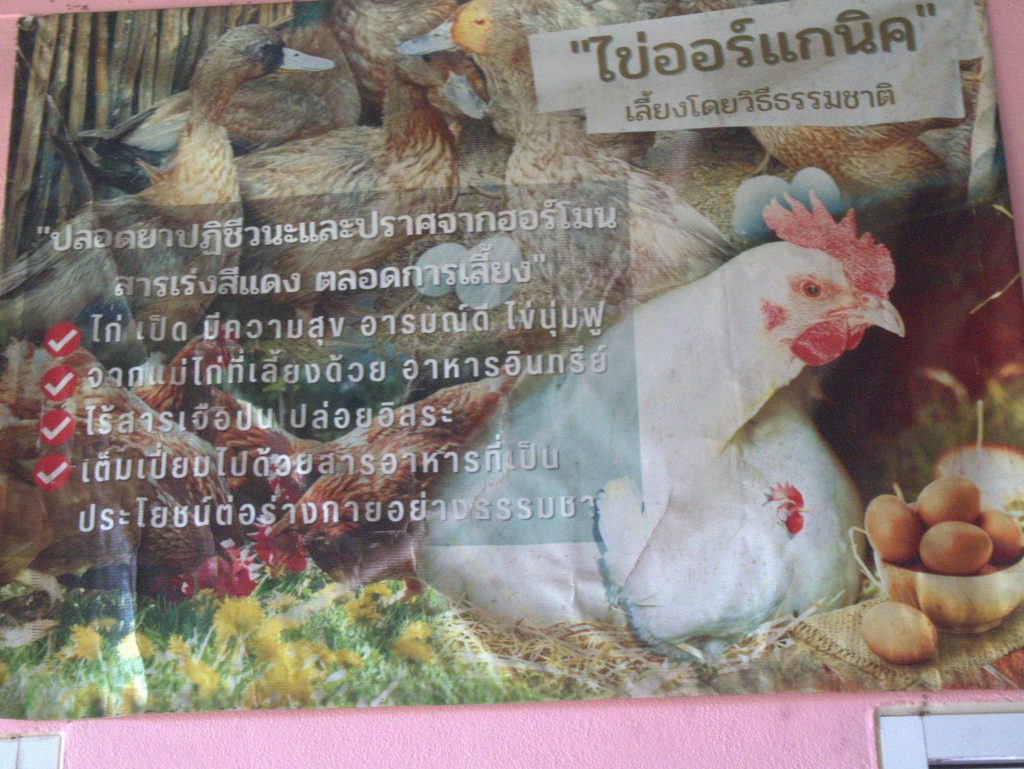

- Creating meaningful and interesting production processes, linked to health, such as “Happy Mood Pork,” “Happy Frog,” organic eggs, and “Indigo Fish,” and “Four Elements” rice.

- Developing animal feed production for pigs, fish, chicken, and frogs.

- Developing rice mixed with herbs for the four elements, along with providing information on the appropriate consumption of rice for each of the four elements: earth, water, wind, and fire, for consumers with different primary elements. Furthermore, a process called “Emerald Green Rice” has been developed, which contains eight times more antioxidants than regular rice.

- Producing sun-dried catfish.

Rice Product Pricing

-Rice pricing is based on production cost data, including rice planting areas, rice varieties, soil preparation, planting, care, harvesting, processing, herbal value enhancement, product design, packaging, and group management. Currently, rice prices are set for each element. A kilogram retail price is 100 baht, 80 baht for wholesale, a half-kilogram retail price is 60 baht, and the wholesale price is 45 baht.

-Marketing and sales channels include creating interesting product titles, such as “Happy Moo” (Pork in a Good Mood). Sales are conducted through community butchering, online communication, and sales to government agencies, academic institutions, and study tour groups.

An important lesson learned from the beginning of raising black pigs or mountain pigs and geese, who roamed the rice paddies to eat. These animals provided manure to improve the soil in the fields intended for rice cultivation. In the first year, the rice suffered from leaf blight. Unsure of how to deal with the problem, as it was the first time the younger generation had farmed, they left it to feed the geese. However, after about a week, the young rice shoots turned green again, allowing them to be harvested. This led to a change in rice farming method to the rice-throwing method. Initially, no one joined the group, but as they gained an understanding of the effects of chemicals and saw examples of chemical-free farming, more people joined.

Promotion and expansion, including community members and individuals, by setting an example. The emphasis will be on producing safe food for family consumption. If the produce is abundant, it can be sold at a shared price. Coordination with local health agencies is required to assess the risks of community members to agricultural chemicals, as well as expanding to external agencies that have provided support, including the Royal Project Foundation (supporting the Meishan pig breed), Maejo University, Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna Chiang Rai, and Mae Fah Luang University.

The Ban Mae Jua Tai Organic Rice Group, located in Village No. 5, Mae Suk Subdistrict, Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, was established in 2007 with the support of the Phayao Provincial Agricultural Office to generate additional income for farmers interested in organic rice farming. The group supports the use of biofertilizers, natural pesticides, and guarantees the purchase price of paddy rice from members. Initially, nearly 100 families were members. After approximately 2-3 years, most members quit, finding it no longer economically viable for their families. Organic rice farming requires more time than chemical farming, lower yields, and this reduces income from rice sales. This also leads to the loss of supplementary income from the family’s primary income-generating activity. (As of September 2025, only one family leader remains.)

The Phayao Provincial Agricultural Office has promoted rice seed production after members ceased to produce organic rice. The office guarantees a higher price for paddy rice than organic rice, offering 25 baht per kilogram to members of the group. However, members ceased the practice after only two to three years, citing the time-consuming and uneconomical nature of the work. Furthermore, seed selection requires considerable effort and time, making it unprofitable for the price and income. Furthermore, the Provincial Agricultural Office has not developed a cost-effective approach for rice farming, including labor and travel costs, land costs, knowledge, and equipment depreciation. Most of the costs are solely calculated for seed, tilling, planting, harvesting, and transportation.

Currently, only one family, a young family, continues to produce seeds for the Phayao Provincial Agricultural Office. Former members remain members; they do not farm organic rice, but produce safe rice. Some are purchased by rice trading companies, but must be processed into milled or brown rice. The buyer also plays a key role in setting the price of rice.

People in Ban Mae Jua Tai, Village No. 5, some former government officials, some retired, and others cultivate organic rice and gardens primarily for family consumption. Some sell souvenirs to relatives and friends. If they have a lot, they will sell them. However, the selling is not focused on price to earn income. Instead, the focus is on providing buyers with nutritious and healthy rice and joining organic rice farming practices.

The possibility of restoring and developing organic rice production in the group, Chak Kineesee sees it as a result of the fact that some young people in the community still produce rice seeds interested in restoring organic rice farming in the community, collaborating with the new generation of the community who used to study and work in big cities and have returned to create new alternative careers in their home communities, interested in healthy food and production that does not create environmental pollution in the community, wanting to produce food and process organic agricultural products.

Currently, some of the projects have been developed to build processing rooms, packaging rooms, sterilization rooms, and storage rooms for Assam tea, meeting FDA standards, for both domestic and export sales. The project aims to cultivate organic Assam tea, owned by a network of Chinese relatives from the same surname, residing in Doi Huai Nam Khun, Mae Suai District, Chiang Rai Province. This area is considered one of the oldest Assam tea sources in northern Thailand. The company also aims to revitalize the production and processing of organic rice, focusing on the health of families and consumers. This is because this new generation is knowledgeable in technology, processing, product design, marketing, and existing international sales channels. They know foreign languages, can easily access various information, and can communicate information through various media that can be communicated across borders.

Therefore, the development approach for organic food production in communities should aim to produce rice for the health of families and consumers, rather than simply selling at a reasonable price. This could involve experimenting with reducing or eliminating the use of chemicals and turning to natural biological methods instead, through work, education, or research with new generation families and families that farm organically for family consumption.

In conclusion, the opportunities for organic farming in the Mekong River Basin still exist. This includes interest from communities and researchers: the gathering of villagers, academics, and international students reflects a shared interest in developing sustainable organic rice; the potential for cost reduction and health care: organic farming reduces reliance on chemicals and increases safety for producers and consumers; the revival and development of indigenous rice varieties: farmers are beginning to prioritize short-lived and extinct traditional varieties; domestic and international market opportunities: there is demand for organic rice from international markets such as Chile, and opportunities to link with other businesses such as Assam tea production; lessons from the past for a new beginning: communities that have received organic rice certification can serve as case studies for new rounds of development for greater efficiency and sustainability.

Report by Chak Kinisi, field survey and data exchange for a case study on organic rice development.

Arranged by Nopparat Lamun, Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge.

(The full report on the research of academics and the project will be presented at a later date.)