From 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. on September 22, the Faculty of Law, Mae Fah Luang University, held an academic seminar titled “Transboundary Toxic Minerals, Traceability Laws, and the Right to Protect the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers.” The seminar also presented the exhibition “Voices of the People & River – Rights of the People and Rights of the River.”

Lecturer Arisara Lekkham, Deputy Dean of the School of Law, reported that heavy metal contamination in the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and northern Mekong Rivers has consistently exceeded water quality standards set by the Pollution Control Department since March 2025. Several media outlets have reported that this is linked to upstream mining activities in the Myanmar border area, which is one of the causes of the contamination. This mining is outside of Thailand’s jurisdiction. Domestic legal frameworks are very restrictive, preventing independent resolution of the problem. Therefore, today, we are considering new perspectives together.

Assistant Professor Dr. Yotsapon Nitiruchiroj, Deputy Dean of the School of Law, opened the event by stating, “Mae Fah Luang University is organizing an academic seminar and exhibition titled “Toxic Minerals Crossing Borders: Traceability Law and the Right to Protect the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers” to commemorate the university’s 27th anniversary. The event was organized by students of the International River Law course. Under the supervision of Professor Arisara Lekham,

Chiang Rai Province is facing the problem of heavy metal contamination in its major rivers, including the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers, which are used by residents for consumption. Continued exposure or consumption of these substances can impact health. Since the recent Songkran Festival, businesses related to the Mekong River have been halted, and agriculture and fisheries have been severely impacted.

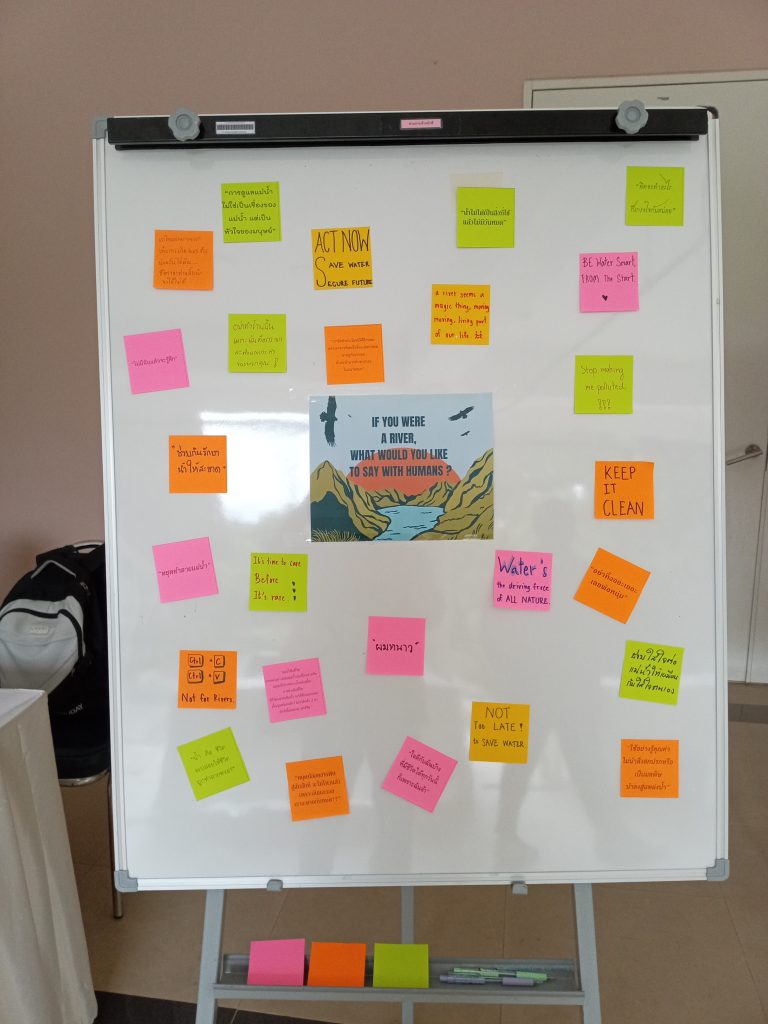

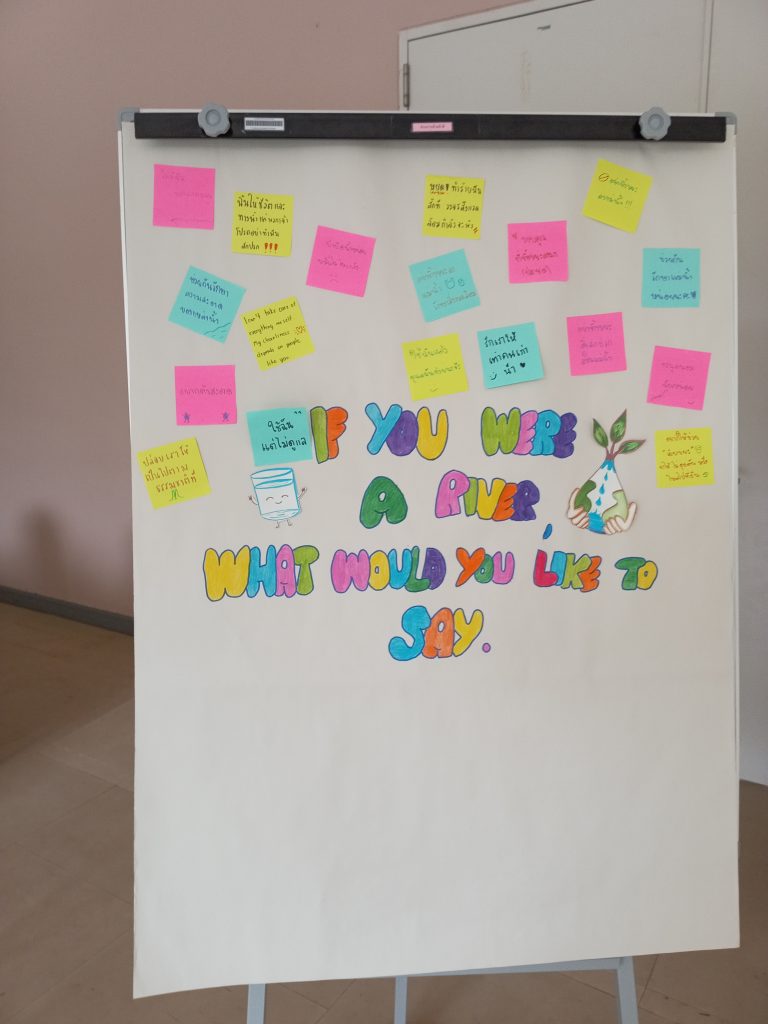

The student exhibitions address three main themes: the rights of the river, the rights of people to access clean water, and the concept of “Voice of the People and River.” This seminar and exhibition aims to address the issues facing Chiang Rai residents and foster collaborative solutions.

The organizers hope that this collaborative effort of academics, experts, the public sector, and students will lead to beneficial proposals for river protection and human rights, and represent an important step for Chiang Rai Province and the region in addressing environmental issues sustainably.

Dr. Suebsakul Kitnukorn, a lecturer at the School of Social Innovation, Mae Fah Luang University, was the first speaker on “Scenario of the Area: Mining and Contamination in the Kok-Sai-Rwak-Khong River Basins”. He opened the discussion by saying:

“There are four models for looking at this problem in terms of complexity and cross-border risks. The first two are border disputes, which should be easily resolved, but the mines affect multiple countries. The second is related to international mechanisms (point sources: regional). The third is that those minerals are not just gold, but also rare earths (Structural: Economic/Political Reform). So what should we do? The fourth and final model posits that rare earths are closely tied to the global energy transition (Global: Planetary Cooperation). So, which model does our problem lie in? All four overlap. If we debate anthropology, is this a problem of Anthropocence or a problem of capitalism?”

This is an interesting question: could mining be a larger structural issue, such as the Anthropocene or capitalism? The speaker emphasized the issue of heavy metal contamination from mining in Myanmar, which has transboundary impacts on Thailand, particularly in the northern region. He highlighted the complexities of addressing the issue both nationally and internationally.

“Are there any guidelines to teach Myanmar to practice clean mining? The UN has it, the OECD has it, and ASEAN has it. The previous government said it would negotiate with Myanmar. We just held negotiations (August 20, 2025) to invite Myanmar to establish a joint committee to monitor water quality because Myanmar says its oil is not above the standard. But we say this is the limit. So where are the mines? What do they look like?”

“There are at least 60 critical minerals involved in the energy transition, and rare earths are one of them.” Rare Earths are part of the global energy transition, making this issue linked to the global energy supply chain, further complicating matters.

Rare Earths are crucial for technologies and energy transitions, such as electric vehicles, which are in high demand. Myanmar is ranked among the top five producers of rare earth minerals in the world, with deposits spread across the country. Mining areas are located near the Thai border, such as Tachileik, and in the headwaters of major rivers, including the Kok, Sai, Ayeyarwady, Salween, and Loi rivers, which flow into the Mekong.

Mining operations are often located within ethnic minority-controlled areas and are under the control of non-state Burmese military forces, making inspection and control difficult. Interference from major powers such as China, the United States, and India, which are involved in exploration and mineral imports from Myanmar, complicates the issue.

Thailand serves as a mineral transit hub. At least 20 Thai companies import minerals from Myanmar, including manganese, lead, copper, tin, and zinc, through border checkpoints such as Chiang Rai, Mae Hong Son, and Tak. Most of the minerals are sent to China, but Thai companies also benefit from this transit. Some celebrities have even reported on social media that they are selling antimony directly. Thailand’s border crossings are not easily monitored due to free trade and transportation agreements.

The lecturer demonstrated widespread water contamination. Google Earth data showed numerous rare earth and gold mines in the Kok and Sai river basins, the headwaters of which flow into Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, and then out to the sea.

The lecturer used maps from the Stimson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based NGO that uses satellite imagery to analyze mining operations in Southeast Asia. The lecturer found 73 mines in the Mekong Basin, along with tributaries in Burma and Laos, and 451 mines in the Ayeyarwady River basin, impacting the entire river, making the turbidity of the water visible. Myanmar’s main river is littered with mines, impacting the Mekong River and its tributaries through Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. Details on rare earth mining in mainland Southeast Asia can be found on the Stimson Center website.

The lecturer also discussed the ambiguity and mismanagement of the Thai government. “Government agencies often report heavy metal levels as “not exceeding the standard” or “no substance detected.” Simple test kits are used to test water, which can only detect arsenic, but not other heavy metals.” The important thing is that it is not complete.

Tap Water: Provincial Waterworks Authorities in areas such as Chiang Rai, Mae Sai, Chiang Saen, and Chiang Khong regularly detect arsenic and barium in monthly laboratory tests (although simple test kits do not detect them). Despite stating that the water quality is “not above standard limits,” the waterworks are considering new sources of raw water, indicating a real problem.

Contamination of aquatic animals and food: Fish samples from rivers were found to contain high levels of mercury, a cause of Minamata disease. The Department of Health has advised against catching fish and aquatic animals from high-risk waters, contradicting the official publicity that “they are safe to eat as they do not exceed the standard.”

Agricultural production: More than 100,000 rai of rice fields and vegetables such as lettuce, chili, mango, and sweet corn grown using water from the contaminated river have been contaminated with arsenic, cadmium, and lead, and many plant samples were found to contain contaminants but were still listed as “below standard”. Farmers have been advised to avoid using water from the Kok River or to use soil amendments, which are difficult to implement in practice.

Results of tests on rice from the previous crop production period found arsenic in rice sent for testing by the Department of Medical Sciences. Urine tests of citizens also found heavy metals, but they were determined to be “not exceeding the standard.”

The speaker questioned the long-term cumulative risks of consuming these substances consistently, even when doses do not exceed the recommended daily limit, and the different effects on each individual’s body.

The first speaker concluded that people in the North, particularly in Chiang Rai Province, face risks from heavy metal contamination in their daily lives, drinking water, food, and the environment. The problem stems from the complexity of managing sources in Myanmar and the response of Thai government agencies, which continue to emphasize that levels of various substances “do not exceed the standard.” While some facts and behaviors of the agencies themselves (such as seeking new raw water sources) clearly indicate problems, people must continue to “live with the risk.”

Lecturer Arisara Lekkham, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Law, who moderated the discussion, explained that she appreciates the opportunity to visualize the current situation in the area. Currently, residents must personally monitor contaminated water, which sometimes exceeds standards. The agricultural and fisheries sectors are assessing the impacts. The cost of monitoring and securing new water sources is a national tax burden, particularly for those directly affected. Important agricultural products, such as rice from Chiang Rai, are not limited to local consumption but are exported nationwide, making contamination a widespread concern. The main issue is that the source of pollution lies outside of Thailand, yet it directly impacts areas within Thailand. The issue is whether mining methods, which may be illegal or unregulated, have led to the contamination. There is considerable interest in the mineral route, from Burma to China, India, and the United States, which are distributing it internationally. Are there any forums addressing the issue of illegal mining, and what are the appropriate approaches and strategies for its future?

Dr. Pete Homchuen, a lecturer in the Department of Mining and Petroleum Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, on “Rare Earth Mining Processes, Chemicals, Traceability, and Contamination Management.”

“Is there anyone who wakes up every day and doesn’t use mineral resources? Everyone has a cell phone, and our phones use rare earth minerals to produce cosmetics and many other things. From the moment we wake up until we go to sleep, we use mineral resources. Let me put it briefly: whether it’s a mine, rare earth minerals, gold, limestone, construction stone, or even sand pits, if operators don’t do it properly, it impacts everyone and the surrounding environment.”

He began by examining the daily reliance on mineral resources. Humans use mineral resources, from the moment they wake up until they go to sleep, whether it’s for mobile phones, cosmetics, or even buildings. Mining has become a necessity, but if it’s not done properly, it can impact the environment and everyone around us, whether it’s rare minerals, gold, limestone, or sand.

Mineral resource ownership and management: Mineral resources do not occur everywhere, but only in certain countries and areas. While Bangkok may not have direct mining operations, people are still affected by resource exploitation. Mineral resources belong to the nation, not to mining companies. Operators are responsible for utilizing the resources and paying royalties, special benefits, and compensation to the state.

Regarding sources of pollution and contamination, arsenic does not only come from mining; it may also come from agricultural pesticides. However, mineral elemental analysis can identify the source of arsenic from the mine. Transporting minerals through Thailand, such as from Laos to Laem Chabang Port, damages Thai roads but does not provide adequate compensation.

Mining operations in some countries, such as Myanmar, may incur high hidden costs for permit applications. This leads operators to attempt to reduce costs by using chemicals such as acids to extract minerals, without adhering to scientific principles. Even though chemical storage tanks lined with plastic or cement can be built in the mine, leakage into the underground or subsurface water, especially when external factors such as heavy rainfall are involved. Relocating the ore processing (purifying the ore) to ensure continuous operation significantly increases transportation costs, potentially up to half the value of the ore, further driving the need for minimum costs.

Regarding pollution control and prevention in Thailand, the professor concluded that Thailand has measures in place to prevent wastewater from mining and mineral processing from being released into the environment. These measures include the construction of sediment retention ponds and a monitoring system. Large-scale mines and metal mines are required to prepare Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA/ESIA) reports and to hold public hearings. Government officials are knowledgeable and capable of monitoring and preventing these incidents by designing systems to accommodate maximum rainfall. However, building sedimentation weirs to address river pollution may not be the answer, and long-term maintenance costs, such as sediment dredging, must be considered. Careful consideration is warranted when deciding.

Ms. Panalee Boonrat, a student at the Faculty of Law and the Student Association for Human Rights at Mae Fah Luang University, talks on “Youth Voices: People’s Rights to Clean Water and a Healthy Environment.”

Human rights are inalienable, including the right to life, good food, and, most importantly, a healthy environment. The United Nations Human Rights Council only approved the “right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment” in 2022 (three years ago). While humans have long coexisted with the environment, environmental rights encompass the protection of a clean, non-toxic environment, sustainable food, clean water, biodiversity, the right to information, the right to expression, and participation.

Ms. Panalee Boonrattan also emphasized that this right is enshrined in the Thai Constitution and in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Article 41 of the Constitution states that individuals and communities have the right to receive public information, but in reality, access to information about the Kok River remains incomplete. Article 43 of the Constitution states that individuals and communities have the right to manage, maintain, and conserve the environment within their communities. Article 57 of the Constitution states that the state has a duty to conserve, protect, restore, and manage the environment.

Regarding the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being: People have the right to good health, but cannot consume fish from contaminated rivers. Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation: River water is so unclean that sometimes people have to buy packaged water for bathing, leaving people in communities near the river with no other options. Goal 13: Climate Change Response: Mining generates burning and dust, contributing to climate change and causing problems such as more frequent flooding.

Ms. Panalee Boonrattan further stated that the current generation (a 20-year-old student) faces environmental problems, such as the inability to play with rainwater as in the past. Air pollution (dust and smoke) has become so severe that it’s become routine and unmanageable. River contamination will have ripple effects down to the ocean, destroying biodiversity and fragile coral reefs. The impacts aren’t limited to Chiang Rai, but extend nationwide and globally. Future generations will grow up in polluted environments, losing their livelihoods and cultures once tied to the river. For example, ethnic minorities living along the Mekong River will no longer be able to allow their children to swim in the river. The river’s importance will diminish, and they may not realize the severity of the problem.

She made a final demand and question: despite human rights, constitutional rights, and the Sustainable Development Goals, these rights are still being unfulfilled. She urged everyone to recognize their rights, and if they can’t stop the problem, they should “join in” to create change, whether through direct advocacy or simply disseminating information to create impact. “Now that we know what our rights are, who will listen to us?” she emphasized the challenges of pushing for change.

Ajarn Arisara Lekkham, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Law, moderator and speaker on “Laws for Transboundary Pollution Management,” summarized the student’s speech, emphasizing that intergenerational awareness and issues are crucial. Youth are becoming more aware of environmental issues such as PM2.5 dust and the impure nature of rainwater, which constitutes intergenerational injustice. They are calling for this situation to be rejected and pushed for change, emphasizing that indifference and lack of change will not solve the problem.

Regarding the limitations of international water legal mechanisms, existing international water law is often limited to member states under agreements such as the Mekong River Commission (MRC), making negotiations with non-member countries such as Myanmar difficult. Consequently, the issue of water pollution from mining has not been seriously addressed in these forums.

Ajarn Arisara recommends shifting the focus to the source of pollution: mining. Since water mechanisms are not yet in place, a shift in perspective should be made to the source of pollution, mining activities, to find alternative mechanisms. She cited the case study of the Trail Smelter, a large zinc and lead smelter in Trail, British Columbia, Canada, which became a major international legal dispute between the United States and Canada in the 1930s. Pollution emissions from the smelter caused widespread damage to crops and property in neighboring Washington State. The Trail Smelter arbitration established the principle that countries have a responsibility to prevent transboundary harm and cannot exercise their sovereignty to ignore pollution caused by other countries.

The principle of “no harm to other states” is a key principle enshrined in customary international law. It states that a state is liable if it fails to control activities within its territory (even those of private companies) that cause harm to another state. The process of resolving this case demonstrates how resolving the issue began with inadequate domestic litigation efforts, through incompetent border committees, and ultimately led to international arbitration. Proving damage can take nearly a century, requiring thorough and reliable scientific evidence to prove a direct link to the harm and lead to compensation claims. This case also led to the establishment of common environmental standards to prevent and control future pollution.

Reviewing the role of Environmental Health Impact Assessments (EIAs/EHIAs), the professor stated, “Although EIAs are domestic law, international legal principles ensure that activities that may cause transboundary harm should be subject to EIAs.” For example, in the case studies of Costa Rica and Nicaragua, road construction without EIAs destroyed wetlands. This leads to claims for damages. Failure to conduct an EIA when transboundary impacts occur could constitute a breach of international obligations and serve as a basis for claims for damages.

The professor views mining as a complex problem with multiple transboundary impacts. Mining is an activity that consumes large amounts of freshwater resources, leading to competition and water contamination. In fragile states or those lacking complete oversight, this could lead to the involvement of capital groups seeking to save money, regardless of the consequences. The failure of domestic regulatory mechanisms has a direct impact on neighboring countries.

Regarding other relevant international mechanisms and instruments, the professor noted the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Aarhus Convention, which provides for the rights of citizens to access information, participation, and environmental justice; the Minamata Convention, which regulates mercury, which relates to gold mining; as well as fundamental human rights, the right to clean water and sanitation; and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which addresses the need for informed consent from local communities. These are mechanisms or conventions of various states.

In the private sector, voluntary standards exist. Some large companies have begun developing voluntary standards and guidelines to demonstrate accountability, such as the Mining and Materials Council and the Responsible Jewellery Council. However, these standards do not yet cover small-scale or illegal mining. Professor Arisara Lekham discussed recommendations and future directions: “The government must continue dialogue and communication with neighboring countries, continuously gathering data and scientific evidence that meet international standards and in a unified manner, to propose common standards or at least allow countries of origin to use their own standards that do not exceed the standard limits. We must take a holistic view of the mining and transboundary pollution problem and elevate it to a threat to public security. For comprehensive and effective management”

The final speaker in the first round was Tara Buakamsri from Climate Connector, on the topic of “Toxic Mineral Routes: Traceability and the Human Rights Business Mechanism.” He explained the complex connections between Rare Earth Elements (REEs), the clean energy transition, environmental impacts, particularly in the Mekong River Basin, and global supply chains. She highlighted the challenges of managing these resources to mitigate the climate crisis without creating new pollution problems.

Let’s start with China’s role in the rise of rare earths. Since Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader, played a key role in opening up China to a modern economy and emphasizing the importance of rare earths in propelling China towards becoming a global power, the rare earth mines in Inner Mongolia’s Yellow River Basin, for example, which produce light rare earths, are a symbol of China’s rise. China regards rare earths as an important resource, distinguished from other regions.

The Importance of Rare Earths in Everyday Life and Clean Energy. Rare earths are key components in modern technologies such as mobile phones (neodymium and dysprosium for vibrations, yttrium for screens) and electric cars, and they are often called the “vitamins of industry” because they are used in small amounts but are crucial to the performance of the products. They play a key role in the rapid expansion of renewable energy sources such as wind turbines and solar panels.

Mr. Tara Buakamsri also explained that polluting mines and the cost of restoring China’s Yellow River system have been severely impacted by rare earth mining, producing mineral deposits, radioactive metals (such as thorium), and soil contamination. The study estimated that restoring China’s polluted river system would take enormous time and money, comparing the restoration costs to the market capitalization of large tech companies (such as Apple) to show that the costs are high, but manageable with commitment, tying in with calls for restoration in Thailand’s Kok, Ruak, and Mekong river systems.

Regarding the supply chain and regional players, China dominates the rare earth supply chain. Key players in the region include Myanmar, Vietnam, and Malaysia. Myanmar and Vietnam primarily export processed rare earths to China. Myanmar has companies like Myanmar Ye Huang Mining Corp., which has mines in Kachin and Shan states. Malaysia is a processing hub for raw materials sourced from Australia, such as Lynas Corp. Ltd. Germany is the largest importer of rare earth magnets from China for the wind turbine industry. Thailand does not mine rare earths but plays a role in importing raw minerals from Australia to upgrade their quality and re-export them.

The clean energy transition requires more essential minerals, but the current recycling rate of these minerals is very low, only 1%, contributing to persistent pollution. However, a lack of robust traceability systems for rare earths makes it difficult to identify legal sources or avoid black market minerals. China’s traceability system is limited to domestic markets.

Ms. Tara Buakamsri suggests utilizing international mechanisms and UN guidelines to address pollution and ensure a just energy transition. He also suggests considering litigation, such as the youth climate lawsuit against the government, as a strategy to raise awareness and raise awareness about the impacts on Chiang Rai’s river system. This includes opening negotiations with China, pointing out that while China has improved its management of pollution from its domestic mines, it must also prioritize the impact of mineral imports from neighboring countries, which will prevent China from being seen as heartless.

Arisara Lekkham, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Law, outlined the challenges of clean energy, stating that while clean energy is the goal, production relies on rare earth minerals. Mineral extraction in poorly managed areas contributes to environmental pollution and human rights violations, particularly for ethnic minorities in Myanmar’s mining areas. It also impacts Chiang Rai. Chiang Rai’s river system, which flows into the Mekong River, has been affected by pollution from Myanmar’s mining operations, putting water quality and agricultural products at risk from heavy metal contamination. Therefore, traceability mechanisms are crucial, using social mechanisms to pressure companies to produce and import certified raw materials that do not pollute or violate labor or environmental rights.

Mr. Tara Buakamsri from Climate Connector added new management ideas: “There are UN guidelines on “no-go zones” and granting legal status to rivers, which are concepts that Thailand could adopt to protect and restore important wetlands, particularly in Chiang Rai.”

Dr. Suebsakul Kitnukorn, a lecturer at the School of Social Innovation, Mae Fah Luang University, presented a second round of urgent recommendations for the Thai government within 4 months as follows:

1) The government should halt all mineral imports from Myanmar through the Thai border from Mae Sai to Mae Hong Son and require importers to declare the source of their minerals to ensure they do not come from polluting sources in the upstream areas of the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers. This aligns with the UN’s principles of responsible business, human rights, and the environment. This also signals Myanmar’s commitment to serious negotiations.

2) Conduct pre-harvest inspections of 100,000 rai of rice fields in the Kok and Sai river basins by October to protect farmers and provide compensation for any contamination. This will ensure consumers and the rice industry in Chiang Rai Province are confident that there is no contamination.

3) Approve a new water supply budget. A budget of 1 billion baht will be allocated to replace contaminated Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong rivers. This will ensure that Chiang Rai residents do not consume tap water contaminated with arsenic and barium.

4) Establish a heavy metal testing center in Chiang Rai Province to provide timely and up-to-date information on contamination in vegetables, fish, water, and the human body. Currently, it must be sent to Bangkok for inspection, taking a long time of 15 days to 1 month, causing the problem to be solved slowly and the information not being up to date.

Arisara Lekkham elaborated further on the issue of the potential for mining in Myanmar and its transboundary impacts. There has been significant investment and interest in Myanmar’s minerals from countries such as China, India, and the United States, which has put pressure on the region’s resources and environment. What models and approaches does this present within the global network? What should we do next?

Dr. Pete Homchuen stated that despite annual regional and global meetings between the public, private, and academic sectors on ASEAN banking, the government must take a clear leading role in promoting cooperation and systematic data collection, such as establishing a heavy metals monitoring center, to ensure traceability and efficient future utilization.

Arisara Lekkham said that while the goal is clean energy, this transition process has increased demand for minerals, which could lead to mining that continues to create pollution and negative impacts.

Ms. Panalee Boonrat, a student at the Faculty of Law and a member of the Student Association for Human Rights at Mae Fah Luang University, stated that while youths cannot solve major problems right now, they can begin by talking and sharing their stories to raise public awareness of the real issues. As awareness expands, new ideas and solutions will emerge, potentially leading to change. Social movements will put pressure on the government, and ultimately, the government must listen to the voices of the people.

Mr. Tara Buakamsri of the Climate Connector said that a new deep-sea treaty has been signed by over 60 countries to protect the oceans and ban deep-sea mining, linking it to the energy transition and pressures from onshore mineral scarcity. Superpowers like China and the United States are facing environmental constraints, prompting China to focus on deep-sea mining, but they are still facing international bans. The pressure from mineral exploration is shifting to the ASEAN region, particularly along Thailand’s borders, which could become a gateway for black markets and smuggling. Thailand should use this opportunity to push for an ASEAN-wide traceability system to prevent smuggling and promote transparency. With a new government and the opportunity for constitutional change, Thailand can use this crisis as a springboard to take a leading role in the region.

Arisara Lekkham, before allowing the audience to comment, explained that in local areas, particularly in Chiang Rai, people are actively pushing for mining and environmental issues, despite being left to the government alone to take responsibility. The fragmentation of national agencies has meant there is no central authority that systematically views mining and links it with health, trade, and the environment. Despite weariness and the perception that change is inevitable, ongoing dialogue and communication within the local community a key force for long-term change.

Kru Daeng-Tuanjai Deetes, a former member of the Senate, stated that the forum was very encouraging in its concrete proposals and its courage to speak the truth. She also expressed her hope that academics from universities with expertise, such as Chulalongkorn University and Chiang Mai University, would collaborate on research, develop technologies, and establish regional and global cooperation networks to systematically propose solutions to the government.

Dr. Pete Homchuen stated that academics are continuously researching mining, the environment, and resource recycling, but there is still a lack of concrete cooperation from the government. Although some projects have been consulted by universities, budget constraints and planning prevent some data from being updated promptly.

Kru Daeng-Tuanjai Deet, a former member of the Senate, asked whether universities could systematically push proposals on toxic substances through the Council of University Presidents of Thailand to advance urgent policy to the government.

Dr. Pete Homchuen said that two months ago, the dean established a working group with Chiang Mai University and the Pollution Control Department to discuss serious solutions, although they have not yet been clearly publicized.

Rakdao Phutchat, of the People’s Network for the Protection of the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers, said that while the 1962 Rio Act stipulates that the state is responsible for transboundary impacts, Thailand has yet to proactively interpret this principle to prevent future catastrophes from toxic buildup or environmental impacts. Experience from many countries around the world clearly shows that ignoring small warning signs can lead to catastrophic damage, and these lessons should be used as a catalyst for policy change. As citizens, we need to urge relevant agencies, such as the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment or the House of Representatives, to step up and take this issue to the international stage to build pressure and foster global cooperation.

Thai PBS reporter Kowit Boontham stated that while there is comprehensive information on toxic substances from research and government agencies, what is lacking is a serious government role in raising the issue internationally. This includes establishing a working group or task force that brings together stakeholders to address the issue systematically and urgently. Allowing toxic substances to accumulate without rigorous supply chain inspections, especially from a superpower like China, could severely impact the people of the Mekong River Basin and ASEAN in the long run. ASEAN should be bold in engaging with China directly to protect the future of the region.

Pranom Chimchaiphum, President of the Chiang Rai Provincial Community Organizations Network, stated that after listening to speakers and reporters reflect on the growing threat of toxic chemicals threatening people’s lives every day, she called on the Thai government to fulfill its constitutional duty to seriously protect public safety, particularly in the Mae KoK, Sai, Rouk and Khong River Basin and Chiang Rai Province, where impacts have already begun. For example, agricultural products have been labeled as hazardous to human consumption, leaving no buyers. Meanwhile, residents have begun to gather with academics and community organizations to demand that government agencies, such as the Pollution Control Department and the Department of Environmental Quality Promotion, take responsibility, and may face legal action through the Administrative Court if they continue to neglect their duties.