Public Consultations on Pak Beng Dam Held in Chiang Khong, Wiang Kaen Raise Cross-Border Concerns

“วิกฤตข้ามพรมแดน – ฉากทัศน์ที่ไม่มีคำตอบ และอธิปไตยจมน้ำของเขื่อนปากแบง: การปรึกษาหารือสาธารณะเกี่ยวกับเขื่อนปากแบงที่จัดขึ้นในเชียงของและเวียงแก่นสร้างความกังวลข้ามพรมแดน”

Article by the Mekong School Team, Lam Phuong Mai, and Daniela Torres Medina – Duke Kunshan University Interns

Figure 1. Presentation of the report by the consulting company

Chiang Khong and Wiang Kaen, Thailand—From June 18 to 21, 2025, the TEAM Consulting Engineering and Management Public Company Limited hosted public consultations on the Pak Beng Hydropower Project (HPP) in various villages from Chiang Khong and Wiang Kaen. Reigniting frustration, distrust, and cross-border criticism, instead of easing public concern. Despite years of community pushback, local villagers, environmental advocates, and regional experts argue that the company has failed to address key transboundary impacts, presented inconsistent data, and demonstrated a lack of sincerity in genuinely engaging with affected communities

The recent consultations aimed to revisit the Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment (TbEIA) and Cumulative Impact Assessment (CIA) of the Pak Beng Dam. This is not the first time such panels have been organized. Similar sessions were held years ago, and despite the repetition, the information presented remains unchanged, incomplete, and some argue, misleading.

“The data they showed us was almost identical to what we saw years ago. Nothing new, no updates, no answers,” said Khru Tee-Niwat RoyKaew, the Chiang Khong Conservation Group chairman and director of the Mekong School: Institute of Local Knowledge. “When we asked about disaster scenarios, fish passage success rates, and the number of people who would lose their homes or jobs if the dam collapses, they had no answers. Why does this keep happening? Where is their transparency?”

Project Overview

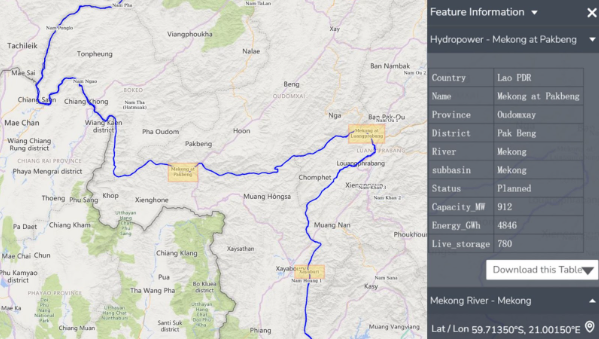

The Pak Beng Hydropower Project is a joint venture between China Datang Overseas Investment Co., Ltd. (51%) and Gulf Energy Development Public Co., Ltd. (49%). The dam will be built on the Mekong River in northern Laos, approximately 35 kilometers upstream from Pak Beng town. It is designed to be 64 meters high and 896 meters long, with a maximum water level of 340 meters above sea level and a reservoir capacity of 559 million cubic meters.

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) was signed on September 13, 2023, establishing a 29-year contract under which 95% of the dam’s electricity output will be sold to Thailand’s Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), starting in 2033 at a rate of 2.70 baht per unit. According to the Mekong River Commission (MRC), the Pak Beng Hydropower Project is a run-of-river dam located on the Mekong mainstream in northern Laos. It has a planned capacity of 912 megawatts (MW), expected to generate an average of 4,775 gigawatt-hours (GWh) per year for domestic use and export.

The project sits between the Jinghong Dam in China and the Luang Prabang Dam and Xayaburi Dam in Laos, creating a cascade system that is already known to disrupt fish migration, sediment flow, and local livelihoods.

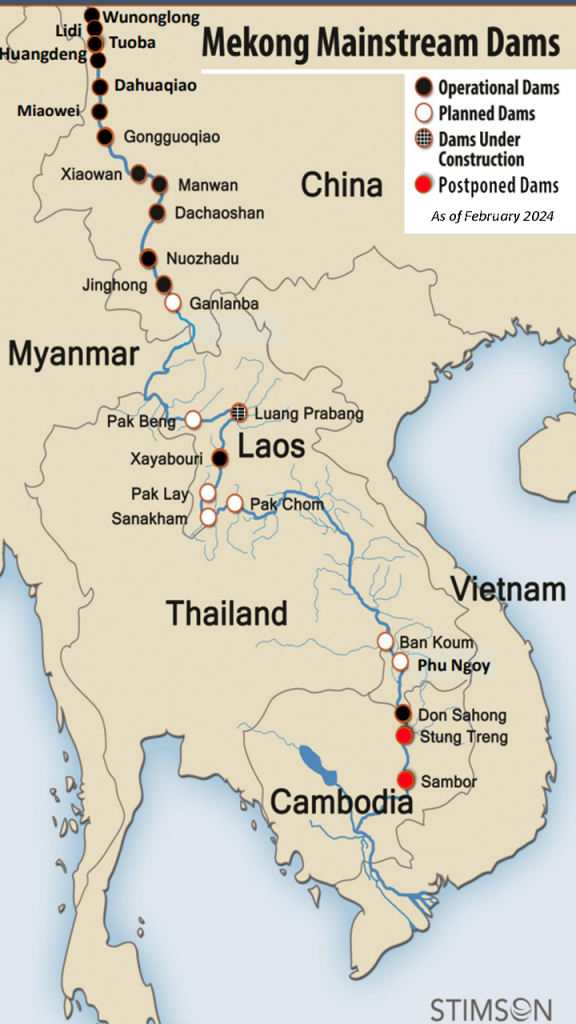

Figure 2. Map of the hydropower plants along the Mekong, operational, planned, and postponed.

(Eyler, Brian. Weatherby, Courtney 2024)

Regional Implications

According to the TEAM Consulting Engineering and Management Public Company Limited project’s Social Impact Assessment, a total of 26 villages along the Thailand and Laos border—covering 923 households and 4,726 people—would be directly impacted by the project. However, the company’s public engagement has so far not included downstream communities in Cambodia and Vietnam, where the dam’s operation will be detrimental to the communities’ livelihood.

The Mekong River is a transboundary ecosystem, vital to millions across China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Experts and local communities are particularly concerned about the dam’s potential to alter the river’s natural flow, especially during the rainy season, with backwater flooding the agricultural land along the Mekong river bank and the tributaries, as the Ngaow River, the Ing River, and the flooding of Boundary markers as Sovereignty drowning.

In Cambodia, the Tonle Sap Lake, the country’s primary source of protein, is at risk due to potential changes in the Mekong’s seasonal pulse, which could damage fish stocks and local economies. The Tonle Sap system supports the livelihoods and food security of approximately 1.2 to 1.5 million people who depend directly on fishing and related activities. In Vietnam, annual flooding and saltwater intrusion have already generated public concern for coastal communities and food production. If the upstream flow is further restricted, these issues could worsen dramatically, putting the livelihoods of millions of people in the Mekong Delta at risk. The region is home to over 17 million people, many of whom rely on rice farming, and freshwater fisheries could be directly affected by changes in river flow. Reduced water availability could jeopardize rice paddies, food production, and the survival of entire coastal villages.

Local Concerns

At one of the consultations in Ban Huai Luk village, a representative of the Mekong River Basin Women’s Group voiced urgent concerns about the dam’s impact on local women’s livelihoods:

“Whether to build a dam or not to build a dam, there are already visible consequences. If the Pak Beng dam goes forward, the occupations of the housewives or women’s groups in Ban Huai Luk fishing along the coast and growing vegetables will be at risk. If this land is damaged due to the dam’s construction, how will it be compensated? Short term? Long term? We don’t want money. We want our land, because that’s how we survive. What about the mothers growing vegetables for their families? Will the housewives have to find new jobs? How will that be compensated?”

Her words reflect the broader failure of the project to account for gendered impacts and informal economies, many of which are deeply tied to the river’s seasonal rhythm which will have irreversible disruptions. Repeated concerns over compensation deal not with the idea of empowering the local economy, but on long term concerns over the production of income directly tied with the administration and production of land which will no longer be available

Despite persistent concerns, company representatives continue to insist that the Pak Beng Hydropower Project will not result in transboundary impacts. However, many stakeholders find this assertion misleading, pointing to a well-documented pattern in which dams on the Mekong have caused widespread severe ecological disruptions and affected communities far downstream—well beyond the immediate project area.

A fisherman from Ban Huai Luk voiced frustration over the lack of transparency and real-world accountability:

“You say fish can pass through the channel at Xayaburi Dam—how many per hour—but why don’t you show the evidence to the public? We fish every day. We used to earn 400,000 to 500,000 baht a year. But this year, prices dropped because toxins were found in the fish.”

“And you talk about a water level of 340 meters. Last year, it flooded up to 357 meters. We’re standing on land now that was underwater last August. You say you’ll release the water in time, who can guarantee that? The Mekong flows too fast. Fish can’t migrate through ladders with this water current. It just doesn’t work.”

According to the Independent Expert Review conducted by International Rivers, the company’s Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment (TbEIA) and supporting documents fail to adequately consider these broader regional effects, raising doubts about the credibility and completeness of their impact analysis.

Figure 3. Map of the hydropower plants in the lower Mekong basin, both in development and finalized. The Pak Beng Dam, Luang Prabang Dam, and Xayaburi Dam are highlighted in yellow (edited).

(Mekong River Commission 2021)

Concerns of Data Gaps and Inconsistent Reporting

Community leaders and experts have pointed out that the environmental and transboundary impact assessments are riddled with inconsistencies and outdated information. The modeling presented by TEAM Consulting ignored major upstream flooding events such as the 2008 flood from the Jinghong Dam, which had severe impacts on downstream Thai communities but were never considered in the company’s analysis.

Even the Mekong’s tributaries, such as the Kok and Ing rivers, were omitted from the sediment and water flow assessments. The company repeatedly dismissed concerns, claiming no transboundary impacts despite failing to provide credible cross-border data.

“Their models didn’t use real, available data,” Kru Tee emphasized. “They didn’t account for the backwater effect, the 12 dams upstream in China, not six as they reported. Their so-called transboundary panel just seems like another checkbox to continue the construction, not a sincere attempt to protect the river or our communities.”

“The ‘transboundary’ label has become a point of contention. In Thailand, this concept is poorly reflected in environmental legislation, leaving communities vulnerable in cross-border disputes where clear protections are lacking.”

Voices from Chiang Khong and Wiang Kaen

At the consultations in Wiang Kaen and Chiang Khong, 8 villagers from Thai JaRoun, Huai Luk, Ban Yai Neu, Jampong, Huai Hean, Pak Ing Tai, Pak Ing Bon, and Don Maha Wan, expressed deep frustration, having seen no concrete action following previous panels.

“We asked the same questions last year. We never received a proper answer about compensation or job replacement for those of us who will lose our livelihoods,” said the village head of Huai Luk, visibly frustrated. “The company keeps avoiding specifics, and we’re tired of being ignored.”

In Huai Luk village, where pomelo farming is the backbone of the local economy, villagers fear that unstable water levels will destroy their crops. Pomelo trees are sensitive to both drought and floods, relying heavily on the Mekong’s groundwater system. Without a stable river, they worry their primary source of income could disappear entirely.

One long-standing concern is the unresolved status of the watershed boundary at Kaeng Pha Dai. If water levels rise, fishing access could be cut off. “The Laos authorities say we can only fish three meters from the Thai side,” said a Ban Huai Luk representative. “So how are we supposed to cross the river and survive?”

He added that border markers remain unfinalized, raising fears they could be submerged during future floods, eliminating any physical reference to territorial boundaries. “There are no activity areas left. This is not solely a short-term issue—it’s a problem that could affect us for thirty or forty years. Who will be left to support us in the aftermath?

In Pak Ing Upper and Lower villages, a different story of abandonment is unfolding. Residents report that no children have been born in the community in over a decade. The collapse of traditional fishing livelihoods, driven by declining fish stocks and blocked migration routes from upstream dams, has pushed the younger generation to leave.

“We are watching our village fade away. This dam will accelerate our disappearance,” said a Pak Ing fisherman.

In Wiang Kaen, JamPong village, residents are increasingly fearful that they must relocate if the Pak Beng Dam is constructed due to the environmental damage the dam will generate. The village is situated between the proposed Pak Beng Dam and another existing dam, placing it at particular risk. Sitting at an elevation of approximately 340–355 meters above sea level, JamPong is especially vulnerable to flooding during the rainy season. Their fears are well-founded. In 2024, JamPong village was severely impacted by the Yagi storm, which brought intense rainfall and flooding that devastated homes, disrupted daily life, and crippled local infrastructure. For many residents, the memory of the natural disaster is still fresh, and the potential construction of the dam has only amplified their anxiety. Villagers worry that by altering the river’s flow and restricting water passage, the dam could make future floods even more destructive and frequent. Importantly, the village serves as a key trading hub for cross-border commerce with Laos. If severe flooding were to occur, trading activities would likely be halted, cutting off a crucial economic lifeline for the region. The potential loss of this trading center would not only harm JamPong residents but would also disrupt commerce and livelihoods on both sides of the border.

Their concerns reflect more than just agricultural and economic risks; they highlight the fragile connection between local livelihoods, cultural identity, and the health of the river. For generations, the community’s survival has been tied to the Mekong’s seasonal rhythms. The proposed dam threatens to disrupt this balance, potentially forcing them to abandon not only their crops but their traditional way of life.

Ignored Transboundary Impacts

While the Mekong River Commission promotes regional cooperation, Cambodia and Vietnam—countries heavily and directly reliant on the Mekong’s seasonal flow—have been included in these public consultations. In Cambodia, there will be a looming ecological collapse in Tonle Sap Lake, a critical source of protein for over a million people, if the river’s seasonal pulse is altered. In Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, threats of worsening saltwater intrusion and reduced freshwater flows could devastate food production and displace millions of people.

While the consultations focused on communities in Thailand and Laos, many participants stressed that the Mekong is a shared river system, not confined to national boundaries. The health of the river affects ecosystems, food security, and cultural traditions across multiple countries. Villagers argue that the project’s risk assessments have failed to adequately consider the interconnectedness of the Mekong’s natural systems, its fisheries, forests, and agricultural zones. They call for a more holistic, transboundary approach to environmental and social impact studies that genuinely involve all affected populations, not just those in the immediate project area.

“Sustainable development must be rooted in respect for all living things and all affected communities,” Bird Researcher and Mekong School Volunteer Chak Kineesee emphasized. “It is not acceptable to prioritize the economic gain of one group while disregarding the well-being of another.”

As the Pak Beng Hydropower Project progresses, many are urging for greater transparency and cross-border dialogue to ensure that the voices of all Mekong River communities are heard and respected.

The combination of environmental vulnerability, past trauma from natural disasters, and the risk to the region’s economy makes the villagers’ situation particularly precarious. For these residents, the dam represents not just an environmental threat but a direct challenge to their future stability and survival.

Gaps and Missing Accountability

The company’s Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment (TbEIA) and public presentations failed to address critical issues:

- No real data on fish migration success rates at existing dams like Xayaburi.

- No sediment transport modeling to assess erosion risks.

- Outdated cumulative impact calculations, ignoring all 12 Chinese dams.

- No serious climate change modeling.

- No detailed compensation or livelihood restoration plans for displaced communities.

- No clear policy on cross-border disaster scenarios.

- No data on heavy metal contamination—arsenic and cyanide levels have already exceeded safety thresholds near Chiang Saen and ChiangKhong.

The absence of this essential information has deepened suspicions that the company’s priority is securing funding rather than safeguarding local communities.

The Broader Implications

At its core, the Pak Beng Dam controversy is about more than just a single project. It is about the right to food, access to resources, environmental justice, and sovereignty across borders. Local villagers, many of whom feel unheard and abandoned, are now calling for stronger legal protections, genuine transboundary cooperation, and real participation in decision-making.

Without this, they say, the Mekong’s fragile ecosystems, cultural heritage, and millions of livelihoods remain under serious threat.

References

Eyler, Brian. Weatherby, Courtney. Mekong Mainstream Dams [map]. Scale not given. Stimson Center, 2024

Mekong River Commission. Lower Mekong Basin (LMB) Atlas. 2021. https://tinyurl.com/Lower-mekong-and-hydropower